As agroecology gains traction in Australia, many farmers and food systems activists have asked what the differences are between agroecology and regenerative agriculture. So today I am going to draw from my PhD literature review to try to answer that question. I do so in the spirit of furthering the movement for ecologically and socially just food and agriculture systems, regardless of where any farmer may presently situate themselves along a continuum of agricultural production.

I am going to take you through what I understand as the history and contemporary state of the rise of alternative agricultures. I then turn to a closer look at regenerative agriculture and agroecology specifically. And I finish with my views on why agroecology offers the transformation our food and agriculture systems need. I do not aim to create divisions in our beautiful fledgling food movement full of hard working and passionate farmers and advocates. On the contrary, I aim to build our collective knowledge, wisdom, and solidarity as we work to radically transform the food system from the ground up. I do not wish to focus on what regenerative agriculture is not but rather on what it can be, and highlight the dangers of corporate capture to these important parallel movements.

A brief history of alternate agricultures

Farmers and researchers have been practising and writing about the need to move away from chemical agriculture for nearly two centuries — all the way back to George Perkins Marsh’s warnings as early as 1864 in Man and Nature — a work credited with launching the modern conservation movement. Agronomist Sir Albert Howard went to India in the first decade of the twentieth century to ‘teach the locals’ how to modernise their agricultural systems, only to be transformed into an advocate of organic agriculture by what he learned there.[1] Along with Rudolf Steiner[2] J.I. Rodale[3], and Lady Eve Balfour[4], Howard is considered one of the founders of the organic movement in the Global North. All promoted the use of composts instead of chemical fertiliser, and focused on the critical roles of humus and mycorrhizal fungi in healthy agroecosystems.

We are in need of a historical corrective here that is as much about today as yesterday. The influence of Indian peasants on the rise of organics in the North is rarely acknowledged. The Green Revolution in India all but decimated small-scale farmers’ traditional, sustainable practices, though the recent farmer protests certainly demonstrate the collective will there to reclaim their right to life and livelihood. While the organics movement has clearly had a net ecological benefit due to reduced use of agricultural and veterinary chemicals (amongst other more sustainable land management practices), what started as a movement has become an industry in its own right. Industrial organics are full of vast monocultures controlled by a decreasing number of corporations. One need only look at the increase in multinational corporations claiming to promote regenerative agriculture to get a taste of what is already happening to this movement (see Walmart, Purina, General Mills, and Danone for just a few, or the consortium that includes Nestle, Unilever, Kellogg, and McCain Foods for another).

There is an effusive and influential popular agrarian literature on the philosophy and practice of what is considered organic, biological, ecological, regenerative, or agroecological farming. This spans the lyrical musings of bucolic life in the country[5], exhortations to diversify to maintain the viability of small-scale farms[6], and socio-political treatises championing the protection of rural communities, local economies, and healthy landscapes[7].

While it can often seem to be the domain of cis-gendered white men, there are many less celebrated women, BIPOC, and queer agrarian (often explicitly anti-capitalist) thinkers and doers to engage with. One I admire is farmer-activist Elizabeth Henderson of Peacework Farm, a pioneering community-supported agriculture (CSA) farm in the American organics movement. Elizabeth has contributed decades of guidance through columns in The Natural Farmer magazine and community-supported publications on CSA, and also as a leading member of Urgenci: the International Network for Community-Supported Agriculture.

Yet while the emergence of the CSA movement in the United States is largely credited to two white-owned farms in the mid-1980s[8], it can also be tracked to Black horticulturalist Booker T. Whatley’s ‘clientele membership club’ established in the 1960s, as recorded in his 1987 guide How to Make $100,000 Farming 25 Acres. Both of these CSA origin stories arise from economic and ecological sustainability narratives and constitute quite radical moves to solidarity economies, as small-scale farmers were rapidly disappearing in the ongoing commodification of food production. However, Whatley’s work included an explicit focus on support for Black farmers who suffered from racialized limited access to government support.

Black farmer-activist Leah Penniman of Soul Fire Farm is a more recent inspiration to many. In 2018 she published Farming While Black, a contemporary practical and liberatory guide to everything from land access to composting. Temra Costa’s celebratory anthology Farmer Jane: Women Changing the Way We Eat [9] profiles 26 women across America farming, cooking, and advocating for change, and Trina Moyles’ Women Who Dig: Farming, Feminism, and the Fight to Feed the World [10] offers a more radical feminist political lens on the efforts of women across three continents farming against the tide of food system injustices.

In Australia, Bruce Pascoe published Dark Emu in 2014, which argues that there is a long history of Aboriginal agriculture, and his and others’ ongoing work to recuperate Indigenous farming practices has had a significant influence within the food sovereignty movement. Pascoe has challenged us with the question, ‘Black people aren’t going anywhere. White people aren’t going anywhere. So what are we going to do about it?’ My PhD project seeks to contribute to working out what we are going to do about it in the context of small-scale farmers with exotic livestock holding title and farming on unceded Aboriginal lands. I will write more on this in a future post.

The origins of regenerative agriculture

Regenerative agriculture’s practices were developed before the phrase was coined by Robert Rodale, J.I.’s son, in the 1980s in the United States[11]. The early works of André Voisin[12] on ‘rational grazing’ (a strong influence on the creator of Holistic Management Allan Savory) remain deeply influential in the regenerative agriculture movement, and spawned an entire education industry around holistic planned grazing of livestock, particularly cattle.

Regenerative agriculture is described by many as an approach to food and farming systems which aims to recuperate biodiversity, soil, water and nutrient cycles, economies, and communities[13]. It has notably grown in public awareness over the past decade, and especially the last few years in Australia, as the country has suffered unprecedented fires while enduring extended droughts. The literature is extensive and still growing. Some of it focuses on farmers’ experiences and reasons for transitioning away from industrial agriculture[14], while much concentrates on the importance of soil[15], or on various techniques[16], and others on regenerative agriculture as a way to mitigate and adapt to climate change[17]. Charlie Massy’s[18] triumphant 2017 account of a dozen broadacre farmers in Australia who have overcome the ‘mechanical mindset’ to farm with nature is arguably one of the most radical of regen ag’s foundational texts, as it actively tackles questions around farmers’ very ways of thinking and being in the world.

Despite these steps forward, many believe that regenerative agriculture remains insufficient. While it accepts the shared biogeological nature of agricultural landscapes, it remains looped into the premises of economic and sociopolitical systems that treat farms and farmers as separate economic units. The two impulses are incompatible. We cannot return to an agriculture that acknowledges a more natural economy defined by a shared ecosystem that still operates under a social system that defines farmers almost entirely as segregated competitors in the market and sectioned-off on the landscape. Such systems reward practices that externalize the damage of such agriculture off-farm and onto our neighbours, both local and global.

Agroecology as ecology and social system

Let me be clear that regenerative agriculture represents a rightly celebrated step forward. There are also other alternatives that can take us a few more steps forward. And I am sure all of us want that.

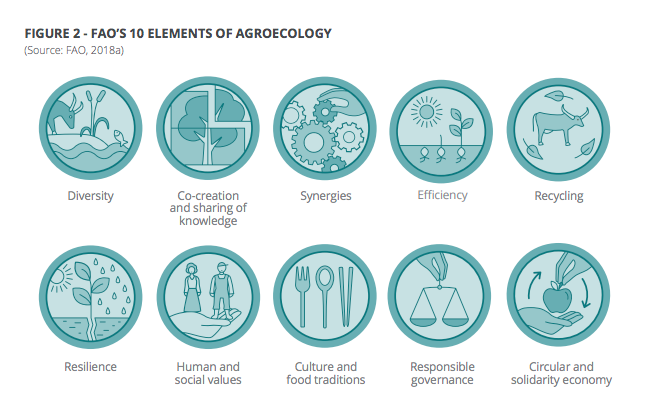

While regenerative agriculture has gained momentum and prominence in Australia, agroecology is much less well-known or understood here, though there is a deep and substantial literature on agroecology internationally. Broadly speaking, agroecology is a scientifically and experientially justified practice of agriculture that is sensitive to the ecosystems in which it is situated and that fosters the democratic participation of farmers in the food system. Its original and still predominant practitioners are Indigenous peoples and peasant smallholders the world over. Many of its advocates make a strong case for relying on peasant and Indigenous knowledge of their land and systems to produce sufficient food sustainably[19]. A science, a set of practices, and a social movement, agroecology is fundamental to my own research project[20], including its concerns with the importance of biodiversity, the role of animals in agroecosystems, and the lived social, economic, and political realities of small-scale farmers.

The term agroecology was coined by Russian agronomist Basil Bensin in 1930, and the practice emerged as more of a social movement in Mexico in the 1970s in resistance to the Green Revolution[21]. Much research has focused on the diversification of agroecosystems over time and space at the field and landscape level, and on enhancing ‘beneficial biological interactions and synergies among the components of agrobiodiversity, thereby promoting key ecological processes and services’[22]. There is also a focus on supporting resource-poor farmers in managing their agroecosystems with minimal inputs[23].

The democratic and ecological potential of agroecology and its political expression in food sovereignty has been well canvassed for decades. There has been an explosion of publications in the last decade that coincided with the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) launched a process and series of global and regional symposia on agroecology in 2014[24]. Political analysis in agroecology extends from Marxist ecological examinations of racism in food and agriculture systems[25], to maintaining the integration of Indigenous peoples and peasants within a matrix of wild and managed ecosystems, to rejecting imperialist attempts to lock up ‘nature’ to protect it from ‘humans’[26]. The concept of ‘nature’s matrix’, in which biodiversity, conservation, food production and food sovereignty are all interconnected goals[27] represents a stark contrast to ‘land-sparing’ arguments that posit humans as separate from and antithetical to the health of functional ecosystems[28]. This debate is currently being played out in the UN’s work on development of the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, with peasants, fisherfolk, and Indigenous peoples defending their rights to customary lands and territories as governments and conservation groups push for further enclosures[29].

Presently there are economic, political, and cultural lock-ins that limit the ability of Australian farmers to shift to agroecology. At the same time, there are what Alastair Iles[30] proposes are enablers. At its core, Iles asserts:

Geographical and environmental conditions have made and are making it hard for farmers to adopt agroecological practices. Strong beliefs among scientist, industry, and government elites in the power of science and technology to overcome climate constraints are leading to agroecology being ignored.[31]

He proposes that some of the implications of neoliberal agriculture policies for agroecology in Australia include:

- Weak farmer resources for adopting agroecological practices;

- demoralized and eroding rural communities; and

- investment in export support instead of environmental support[32].

In turn, enabling dynamics for an agroecological transition include:

- crises;

- coalescing social organization;

- effective agroecological practices;

- external allies; and

- favourable policies[33].

All of the above enablers are currently coalescing in Australia under:

- a global pandemic;

- strengthening global and national food sovereignty movements;

- the emergence of agroecology schools such as those run by the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA); and

- increasingly supportive state governments offering targeted support for small-scale farmers[34].

Food sovereignty embodies the collective politicisation of agroecology. It asserts everyone’s right to nutritious and culturally appropriate food produced and distributed in ethical and ecologically sound ways, and our right to democratically determine our own food and agriculture systems[35]. With its political roots established in the mid-90s in the fertile soils of La VÃa Campesina (LVC) – the global alliance of peasants – food sovereignty was launched into public political discourse at the World Food Summit in Rome in 1996[36]. In the words of McMichael, ‘food sovereignty emerged as the antithesis of the corporate food regime and its (unrealized) claims for “food security” via the free trade rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO)’[37].

Agroecology fundamentally aims to promote the deep ecological, social, and economic knowledge of First Peoples, peasants, and other small-scale food producers and custodians of land. It puts decision making power back in the hands of Indigenous Peoples and peasants and local communities.

Regenerative agriculture is promoted and practised by many who are thinking and acting in much more holistic ways than industrial agriculturalists, but as a peoples’ movement, the approach presently lacks coherence and cohesion. Too much of what I see promoted as regenerative agriculture is still just capitalist agriculture with better inputs. Its ecological work is important but ultimately iterative rather than transformational because of its lack of a political framework. In a critical way regen ag is repeating the errors of the organics movement. Organics were commodified and consolidated because the sector lacked a collective vision to unshackle itself from capitalist food systems.

To my knowledge, regenerative agriculture has not developed a theory of change for an economic or social transformation, and is growing a new generation of ‘experts’ and gurus who profit from teaching the how rather than the what or why. This is a critical juncture for regen ag – can it shift to teaching the ‘what’ as well as the ‘how’? Who will its teachers be? Will they accept the challenge to think and advocate beyond farm boundaries to the broader social and political economies and ecologies within which farmers care for country?

Agroecology, on the other hand, has a well-developed theory of change. It works to support horizontal knowledge sharing by empowering farmers and their communities to learn from and with each other and the land and all on it, rather than relying on external experts for inputs of knowledge or other resources.

Further, by collectivising and uniting the voices of the people in democratically constituted organisations like the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA), and actualizing shared decision-making, agroecology offers genuine political strength and capacity for policy reform as well as grassroots transformations. A major strength of agroecology is that it is immune to being captured as a brand due to its grassroots, democratic principles and practices – nobody can own or certify agroecology because it asserts everybody’s right to practice it without reliance on or creation of externalities.

My intentions are altruistic. I do not aim to divide us, but rather to help understand our histories and ways forward from here. Our objective should be to offer every kind of farmer a path to the next food landscape forward. Regenerative agriculture and agroecology proponents and practitioners ultimately want food and agriculture systems that are ecologically sound and socially just. If we work together, actualizing everyone’s right to nutritious, delicious, and culturally appropriate food produced and distributed in ethical and ecologically sound ways, Australia can get there.

Endnotes

[1] Howard 2010, 2011

[2] 1974

[3] 1945

[4] 1975

[5] E.g. Bromfield 1976, 1999, 2015; Seymour 1974; Berry 2004

[6] E.g. Henderson 1943, 1950; Whatley 1987; Salatin 2006

[7] E.g. Berry 2002; Rebanks 2015; Smaje 2020

[8] McFadden 2004

[9] 2010

[10] 2018

[11] Gosnell, et al 2019

[12] 1957, 1958, 1962

[13] Massy 2017; Brown 2018; Fernandez Arias, Jonas & Munksgaard 2019

[14] Massy 2017; Gosnell 2019

[15] Brown, 2018; Masters 2019

[16] Sherwood 2000; Rhodes 2017

[17] Gosnell et al. 2020; Toensmeier 2016

[18] Call of the Reed Warbler

[19] Scott 1998; Rosset & Altieri 2017; Anderson et al 2021; Liebman, et al 2020

[20] Wezel, Bellon & Doré 2009

[21] Gliessman 2013; Giraldo & Rosset 2017

[22] Rosset & Altieri 2017: 20

[23] Rosset 1990; Altieri 1990, 1995, 2017; Gliessman 2006

[24] Agarwal 2014; Alonso-Fradejas, et al. 2015; Rosset & Altieri 2017

[25] Chappell 2017, 2019; Montenegro de Wit 2020

[26] Gliessman 20016; Philpott, et al 2008; Perfecto & Vandermeer 1995; Perfecto, Vandermeer, & Wright 2009; Liebman, et al 2020

[27] Perfecto, Vandermeer & Wright 2009

[28] Wilson 2016

[29] IPC 2021; Pascual et al. 2021

[30] 2020

[31] Iles 2020: 5

[32] Iles 2020: 5

[33] Mier Y Teran Cacho et al. 2018; Anderson et al. 2019; Iles 2020

[34] Agriculture Victoria 2021

[35] IPC 2015

[36] Alonso-Fradejas, et al. 2015

[37] 2015: 934

References

Alonso-Fradejas, A., S. M. Borras, T. Holmes, E. Holt-Giménez and M. J. Robbins. 2015. “Food sovereignty: convergence and contradictions, conditions and challenges.” Third World Quarterly 36(3): 431-448.

Altieri, M. and E. Holt-Giménez. 2016. “Can agroecology survive without being coopted in the Global North?” SOCLA paper.

Agriculture Victoria. 2021. Small-scale and Craft Program. < https://agriculture.vic.gov.au/support-and-resources/funds-grants-programs/small-scale-and-craft-program>, [accessed 14/6/21].

Anderson, C.R., Bruil, J., Chappell, M.J., Kiss, C., & Pimbert, M.P. 2017. From Transition to Domains of Transformation: Getting to Sustainable and Just Food Systems through Agroecology, in Sustainability 11 (19), 5272.

Anderson, C.R., Bruil, J., Chappell, M.J., Kiss, C., & Pimbert, M.P. 2021. Agroecology Now! Transformations Towards More Just and Sustainable Food Systems, Palgrave Macmillan.

Andrée, P., Dibden, J., Higgins, V., & Cocklin, C. 2010. ‘Competitive Productivism and Australia’s Emerging ‘Alternative’ Agri-food Networks: producing for farmers’ markets in Victoria and beyond, Australian Geographer, Vol. 41, No. 3, pp.307-322, September 2010.

AFSA (Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance). 2018. Major win for food sovereignty as Victoria announces planning reforms, < https://afsa.org.au/blog/2018/06/27/vicplanningreforms/> , [accessed 6/6/21].

Balfour, E. 1975. The Living Soil and the Haughley Experiment, London: Faber and Faber.

Berry, W. 2002. The Art of the Commonplace: The Agrarian Essays of Wendell Berry, Counterpoint Press.

Berry, W. 2004. That Distant Land: The Collected Stories, Counterpoint Press.

Bromfield, L. 1976. Out of the Earth. Wooster Book.

Bromfield, L. 1999. From my experience. Wooster Book.

Bromfield, L. 2015. Malabar Farm. Wooster Book.

Calvário, Rita. 2017. ‘Food sovereignty and new peasantries: on repeasantization and counter-hegemonic contestations in the Basque territory’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, DOI: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1259219

CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity). 2020. Preparations for the Post-2020 Biodiversity Framework. https://www.cbd.int/conferences/post2020 (accessed 28/3/2020).

Costa, T. 2010. Farmer Jane: Women Changing the Way We Eat, Gibbs Smith Press.

FAO. 2019. The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture, J. Bélanger & D. Pilling (eds.). FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. http://www.fao.org/3/CA3129EN/CA3129EN.pdf (accessed 3/3/19).

Fernandez Arias, P., Jonas, T., Munksgaard, K. 2019. Farming Democracy: Radically Transforming the Food System from the Ground Up, Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance.

Giraldo, O.F, & Rossett, P.M. 2017. ‘Agroecology as a territory in dispute: Between institutionality and social movements.’ Journal of Peasant Studies. [online] DOI:10.1080/03066150.2017.1353496.

Gliessman, S. 2013. Agroecology: Growing the Roots of Resistance, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 37:1, 19-31

Gosnell, H., Gill, N., Voyer, M. 2019. ‘Transformational adaptation on the farm: Processes of change and persistence in transitions to ‘climate-smart’ regenerative agriculture’, in Global Environmental Change, Volume 59, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101965.

Gosnell, H., Charnley, S. and Stanley, P. 2020. Climate change mitigation as a co-benefit of regenerative ranching: insights from Australia and the United States. Interface focus, 10(5), p.20200027.

Heckman, J. 2006. A history of organic farming: Transitions from Sir Albert Howard’s War in the Soil to USDA National Organic Program. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems. 21. 143 – 150. 10.1079/RAF2005126.

Henderson, G. 1943. The Farming Ladder. Faber and Faber.

Henderson, G. 1950. Farmer’s Progress. Faber and Faber.

HLPE. 2019. Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome.

Howard, A. 2010. An Agricultural Testament. Oxford City Press.

Howard, A. 2011. The Soil and Health: A Study of Organic Agriculture. Oxford City Press.

Iles, A. 2020. ‘Can Australia transition to an agroecological future?’ AGROECOLOGY AND SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEMS https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2020.1780537

IPC (International Planning Committee on Food Sovereignty). 2021. IPC Declaration Agenda Item 7: Biodiversity and Agriculture, Informal session of the Twenty-fourth meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA-24), 25 February 2021, https://www.foodsovereignty.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2021_02_24_IPC-statement_Item-7_biodiversity-and-agriculture_informal-SBSSTA.pdf, accessed 5/6/21.

IPC (International Planning Committee on Food Sovereignty). 2015. ‘Report of the International Forum for Agroecology, Nyéléni, Mali, 24-27 February 2015.’ < https://www.foodsovereignty.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Download-declaration-Agroecology-Nyeleni-2015.pdf> accessed 5/6/21.

Jonas, T. 2017. ‘Victorian Government Welcomes Feedlots and Rejects Free Range Pigs and Poultry’ Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance. https://afsa.org.au/blog/2017/10/02/victorian-government-welcomes-feedlots-rejects-free-range-pigs-poultry/ (accessed 26/3/2020)

Liebman, A., Jonas, T., Perfecto, I., Kelley, L., Peller, H.A., Engel-Dimauro, S., Rhiney, K., Seufert, P. Fernando Chaves, L., Bergmann, L., Williams-Guillén, K., Ajl, M., Dupain, E., Gulick, J., Wallace, R. 2020. Can agriculture stop COVID-21, -22, and -23? Yes, but not by greenwashing agribusiness, PReP Agroecologies, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1M-yW7JakFwSV_ZFUNZdQLdYWhlbn_L6D/view [accessed 15/12/20]

Lockie, S. 2009. ‘Agricultural Biodiversity and Neoliberal Regimes of Agri-Environmental Governance in Australia’, Current Sociology, May 2009, Vol. 57(3): 407–426.

Marsh, G. P. 2003. Man and Nature, University of Washington Press.

Massy, C. 2013. Transforming the Earth: A Study in the Change of Agricultural Mindscapes, PhD thesis, ANU.

Massy, C. 2017. Call of the Reed Warbler: A New Agriculture, A New Earth. UQP, Canberra.

Masters, N. 2019. For the Love of Soil: Strategies to Regenerate Our Food Production Systems, Printable Reality.

McFadden, S. 2004. ‘The History of Community-Supported Agriculture’, Rodale Institute, < https://rodaleinstitute.org/blog/the-history-of-community-supported-agriculture/> [accessed 6/6/21].

Mier y Teran G.C., Mateo & Giraldo, O. & Maya, E. M. & Morales, H. & Ferguson, B. & Rosset, P. & Khadse, A. & Campos-Peregrina, M. 2018. Bringing agroecology to scale: key drivers and emblematic cases. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. 42. 1-29. 10.1080/21683565.2018.1443313.

Montenegro de Wit, M. 2020. What grows from a pandemic? Toward an abolitionist agroecology, THE JOURNAL OF PEASANT STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1854741

Moyles, T. 2018. Women Who Dig: Farming, Feminism, and the Fight to Feed the World, University of Regina Press.

Muir, C. 2014. The Broken Promise of Agricultural Progress: An environmental history, Routledge.

Penniman, L. 2018. Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land, Chelsea Green.

Perfecto, V. 2009. Nature’s Matrix: Linking Agriculture, Conservation and Food Sovereignty. In Nature’s Matrix. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849770132

Plumwood, V. 1993. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. Routledge, London & New York.

Rebanks, J. 2015. The Shepherd’s Life: A Tale of the Lake District, Penguin.

Rhodes, C.J., 2017. The imperative for regenerative agriculture. Science Progress, 100(1), pp.80-129.

Rodale, J.I. 1945. Pay Dirt: Farming & gardening with composts, New York: Devin-Adair Company.

Rosset, P., Altieri, M. 2017. Agroecology: Science and Politics, Fernwood Publishing.

Salatin, J. 2006. You Can Farm: The entrepreneur’s guide to start and succeed in a farming enterprise, Polyfaces, Inc.

Scott, J. C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press, Durham.

Seymour, J. 1974. The Fat of the Land. Faber and Faber.

Sherwood, S. and Uphoff, N., 2000. ‘Soil health: research, practice and policy for a more regenerative agriculture’. Applied Soil Ecology, 15(1), pp.85-97.

Steiner, R. 1974. Agriculture. Biodynamic Agricultural Association.

Toensmeier, E., 2016. The carbon farming solution: a global toolkit of perennial crops and regenerative agriculture practices for climate change mitigation and food security. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Vandermeer, J. 2013. The ecological basis of alternative agriculture, in Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 26 (1), 201-224.

Van der Ploeg, J. D. 2018. The New Peasantries: Rural Development in Times of Globalization, 2nd Edition, Routledge.

Wallace, R. 2016. Big Farms Make Big Flu: Dispatches on infectious disease, agribusiness, and the nature of science. Monthly Review Press.

Wallace, R., R. Alders, R. Kock, T. Jonas, R. Wallace, and L. Hogerwerf. 2019. “Health Before Medicine: Community Resilience in Food Landscapesâ€, in One Planet One Health, Sydney University Press. ISBN 9781743325377

Wallace, R. G., Liebman, A., Weisberger, D., Jonas, T., Bergmann, L., Kock, R., & Wallace R. 2021. ‘Industrial Agricultural Environments’ in Routledge Handbook of Biosecurity and Invasive Species, eds. Kezia Barker & Robert A. Francis, Routledge.

Wezel, A., Bellon, S., Doré, T. et al. 2009. ‘Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice’. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 29, 503–515.

Whatley, B. T. 1987. How to make $100,000 on 25 acres, Regenerative Agriculture Association of Rodale Institute.